In Tenderness, a novel about a novel, Alison MacLeod explores how Lawrence’s most famous work, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, has come to mean so many things to so many people since it was privately published in 1928. Flipping across time periods, Macleod explores the creation of the novel, the banning of it, and how it continued to be used as a tool of suppression right up to the infamous obscenity trial of 1960 when Allen Lane risked imprisonment for freedom of expression. It touches on the lives of Jackie O, J Edgar Hoover, and Lawrence at pivotal moments of his short life.

On January 2, 1960, John F. Kennedy announced his candidacy for the presidency of America and launched his campaign nationwide. At his side was his glamorous and highly respected wife, Jackie O. J Edgar Hoover is convinced this liberal couple are a threat to American values of decency and so begins compiling evidence against them. Meanwhile at the Old Bailey, London, a week or so before the presidential elections are announced, Penguin books stands trial for obscenity.

MacLeod deftly weaves these facts and characters together to show how one book has come to be used as a tool of suppression for various causes. There’s a bit of fudging with the chronology of events and some artistic license with regards to conversations and meetings, but these are calculated imaginative risks that remain true to the essence of the events and people described.

MacLeod imagines Jackie O in the public gallery of the GPO in 1959, listening into the trial of Lawrence’s novel. There is no record of who was in attendance, but as Jackie O was a vociferous reader, it is likely she would have been very interested in the outcome. We are given insight into her fascination with literature through meetings with the esteemed literary critic Lionel Trilling, who, in real life, was a regular guest at The White House. Jackie O asks Trilling, “How can we as people come to love variousness and difficulty—in the way we do in literature and stories and poetry—when we are in love with modern conveniences” which mirrors sentiments espoused by Lawrence earlier in the novel when he says: “People now had more and more—bigger houses, proud water closets, stuffed furniture, new motor-cars—but they no longer knew how to feel alive in their lives.”

J Edgar Hoover was obsessed with the trial and was convinced the book would remain banned. He believes associating Jackie O with Lawrence will prove her immorality to the American public. We know from history that Hoover – who served under eight presidents – will stop at nothing in his quest for victory. His tactics include intimidation, blackmail, and illegal surveillance. MacLeod insinuates that Hoover’s moral crusades against perceived vice may have been due to a repressed homosexuality which adds another layer of complexity to the novel and the motivations of those affected by it.

Reading this in 2023 is uncanny. Hoover’s crusade against liberal democratic values lives on in the populist tirades of Donald Trump and the banning of books from schools in America that are deemed to promote sexual and gender pluralities. Last year there were requests to ban 2,571 books in libraries across America. It is a curt reminder that we need to be more tender than ever towards people who are different to us and avoid moral purity at all costs.

MacLeod interjects various aspects of Lawrence’s life into the novel, most admirable of which involves a key witness in the Lady C trial who shows tenderness by standing up for Lawrence despite being betrayed by him when he represented a deceased family member of theirs in a short story published in England, my England and Other Stories (1922). There’s also compelling evidence as to the true inspiration for Lady C.

But most impressive of all are the scenes from the 1960 trial. MacLeod plonks the reader right in the centre of the court to bear witness to the outrageous bias of the judge which left me momentarily doubting the evidence, despite knowing the outcome.

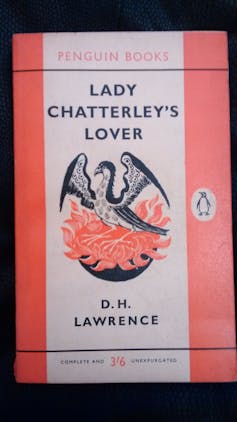

Lady Chatterley’s Lover was accused of many things. Yet this perhaps tells us more about the prejudices of the reader than the author. Lawrence described the novel as being a bomb, hoping it would explode and create something new, something better than the mechanical modernity that was slowly dehumanising man. The novel was so important to him, that he wrote three versions. The middle version, Tenderness, was a tentative title suggested in a letter to Dorothy Brett, the artist who would relinquish her status as daughter of Viscount Esher and follow Lawrence to New Mexico in 1924 in search of Rananim.

In Lady C, Lawrence was attempting something far more radical than pornography. He was putting forth a philosophy of how to live against the backdrop of an illegitimate relationship that cut across the classes. Tenderness to Lawrence was about emerging from vulnerability and difficult experiences to forge a new existence. To some extent this was a continuation of sentiments raised in Look! We have come through! (1917) a kind of manifesto for enduring the good and bad times in a relationship knowing it will eventually ‘transcend into some kind of blessedness.[i]’

The Penguin trial ushered in the permissive society and greater sexual freedom. But this did not mean ‘blessedness’ for everyone. J.F. Kennedy would be murdered in 1963, a few years after his election victory. The only way to deal with people who are too alive, it would seem, is to kill them. Penguin may have won the Obscenity Trial, but Lawrence’s battle still goes on.

[i] D.H. Lawrence. Look! We have come through! 1917.