Frustrated with modernity and the literary establishment, D.H. Lawrence travelled the globe in search of Rananim. He believed a new way of being was possible, making this the philosophical focus of his novels. Can his ideas on community help us during these difficult times? Expect a few tantrums on the way…

Although he would have enjoyed the solitude, D.H. Lawrence wouldn’t have coped very well with lockdown. Not because he was rubbish at following rules, but because he was a proper fidget. After leaving Britain in 1919 he travelled the globe, never settling in one place for more than two years. He refused to own property, making home in disused cabins at the top of mountains or being put up by friends. There were numerous reasons for his peripatetic lifestyle, but here we’ll focus on one: Rananim.

It’s believed that Lawrence first came across the concept of Ranamim when his friend S.S. Koteliansky sung the Hebrew chant Ranani Zadikim l’Adonoi to him. The two met in 1914 and were together in Barrow-in-Furness when WWI was declared. This was a significant time to bond as it marked a very difficult period for Lawrence as he suffered from poverty, political persecution – his wife was German, and frustrations with the censor that would plague his entire career. This is best captured in a letter to Edward Garnett in June 1912, when Lawrence really let rip:

“Curse the blasted, jelly-boned swines, the slimy, the belly-wriggling invertebrates, the miserable sodding rotters, the flaming sods, the snivelling, dribbling, dithering palsied pulse-less lot that make up England today. They’ve got white of egg in their veins, and their spunk is that watery it’s a marvel they can breed. They can but frog-spawn — the gibberers! God, how I hate them! God curse them, funkers. God blast them, wish-wash. Exterminate them, slime.”

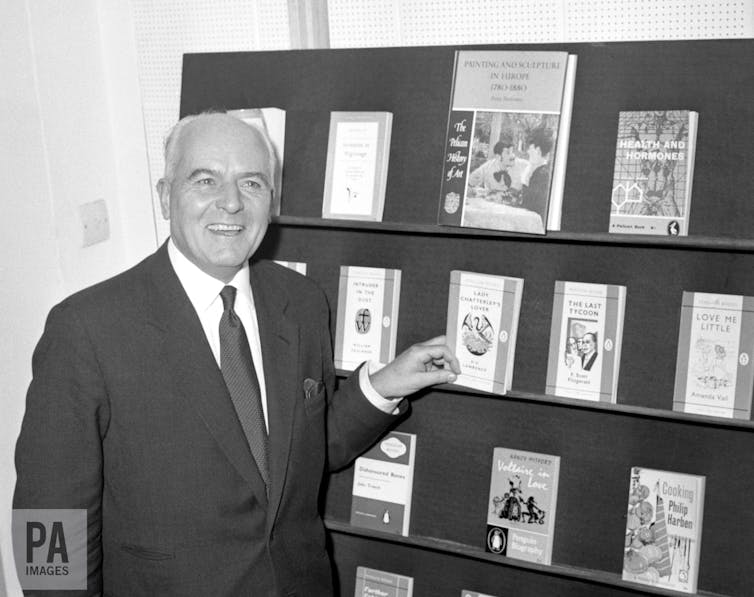

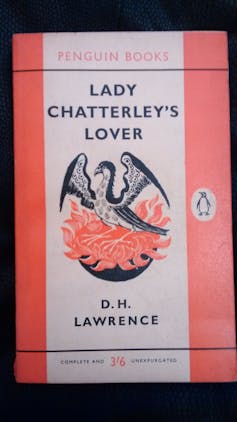

This letter was in response to publisher William Heinemann who had rejected the first draft of his third novel, Sons and Lovers. This was eventually published in 1913 but it didn’t take long for it to be banned from libraries. His next novel, The Rainbow (1915) was seized under the Obscene Publications Act and burned. Although it didn’t contain any naughty words, it was deemed anti-British for daring to question everyday fundamentals such as work, religion, and relationships.

Lawrence was as frustrated with the publishing industry as he was with modernity. Industry dehumanized community and destroyed the natural landscape, whereas war demanded blind conformity to the flag and a further loss of individuality. He felt like he was the only one who could see this ‘Ugliness. Ugliness. Ugliness’ and so began to develop a philosophy for life through his novels. To do this he had to get away from Britain sharpish, and so embarked on a ‘savage pilgrimage’ of self-imposed exile.

“I shall say goodbye to England, forever, and set off in quest of our Rananim” he wrote to Koteliansky, on 12 January 1917. Rananim was the concept of a utopian community, a place where humanity could rise from the ashes of the past and old values, and purged of evil, be reborn in peace and love. Away from modernity and consumerism, it would be possible to find “a good peace and a good silence, and a freedom to love and to create new life.” The phoenix became his personal emblem, as he too was rising out of the flames and being reborn.

It would be a mistake to interpret this as the desire to create some kind of hippy commune or scribal gathering. This is evident from Lawrence’s time in Taos, New Mexico. Mabel Dodge Luhan, a wealthy patron of the arts, invited the Lawrence’s to stay with her in 1921. She wanted him to capture the spirit of Taos in the same way that he had done with Sea and Sardinia (1921). She too was trying to escape modernity and believed that bringing the greatest thinkers and artists together in one place would help build a better world than the one currently being destroyed by war and industry.

Lawrence was apprehensive at first, asking whether he’d encounter “a colony of rather dreadful sub-arty people”. He wasn’t a fan of literary crowds who he described as “smoking, steaming shits”. He was also cautious of “meeting the awful ‘cultured’ Americans with their limited self-righteous ideals and their mechanical love-motion and their bullying, detestable negative creed of liberty and democracy.” But he eventually turned up a year later after taking a detour via Australia and Ceylon.

There was an immediate clash of personalities and they quickly fell out. He hadn’t travelled halfway across the world to further her status. So, he headed off to the hills to live in a cabin. It was here, away from the crowds, that he was truly happy, embarking on a series of DIY projects – carpentry, glazing and putting up shelves, living simply and writing under a tree.

We are being asked to self-distance at the moment and many of us our finding it difficult. But Lawrence chose to get as far away from people as he could, writing, “I only want one thing of men and that is that they should leave me alone”. What he really meant was anybody who banned his books or didn’t share his world view.

His search for kindred spirits took him to many countries, but it never quite worked out. At his most desperate he considered ploughing his savings into a boat, “I would like to buy a sailing ship and sail among the Greek islands and be free…free! Just to be free for a little while of it all…with a captain and a couple of sailors, we could do the rest.”

Lawrence teaches us to seek out Rananim in our lives. We may not have the freedom to replicate his nomadic lifestyle, but we are starting to think about what community means, or, at the very least, have introduced ourselves to the neighbours for the first time.

Rananim doesn’t exist in a single place or location, location, location – so don’t expect Kirstie Allsop to source it out for you. Rather it’s a state of mind shared with likeminded people. So, don’t expect to find it too soon. In a letter to Catherine Carswell he explains, “I think people ought to fulfil sacredly their desires. And this means fulfilling the deepest desire, which is a desire to live unhampered by things which are extraneous, a desire for pure relationships and living truth”.

Lawrence lived through the Spanish Flu outbreak of 1918 which killed 50 million people – more than died in WWI. He had terrible health throughout his life and eventually succumbed to tuberculosis at the age of 44. He was not happy with the world he was born into, or perhaps more accurately, unhappy with the way that world was being destroyed by industry, pollution and greed. Sound familiar?

It seems fitting, then, that during lockdown, where everything “extraneous” has been removed, the rainbow, the title of Lawrence’s 1915 novel, has become the symbol of hope during these difficult times. This once banned book which dared to demand a different way of being holds a message in the final paragraph that we can all relate to.

“She saw in the rainbow the earth’s new architecture, the old, brittle corruption of houses and factories swept away, the world built up in a living fabric of Truth, fitting to the over-arching heaven.”

This article was originally published on the Nottingham UNESCO City of Literature websitein response to the challenges presented by coronavirus.

In the D.H. Lawrence Memory Theatre we are exploring Lawrence life through artefacts. We officially set sail in November 2019 to mark the centenary of his self-imposed exile. You can submit artefacts here, or join in the conversation on Instagram or leave a comment below.